- The Global Reforestation Organization Directory provides standardized information on more than 125 major tree-planting organizations, making it easier for donors to compare groups and find the ones that match their priorities.

- Researchers from the University of California Santa Cruz evaluated groups across four categories: permanence, ecological, social and financial, each backed by scientific literature on best practices.

- Much of the evaluation relies on the organization’s self-reporting through surveys or website statements and, while researchers acknowledge this limitation, they say it still provides a valuable framework and a starting point for donors.

- The directory doesn’t rank organizations but rather shows what organizations publicly share about following scientific best practices, avoiding common mistakes and monitoring their results.

Planting trees is something most people can get behind, and tens of thousands of reforestation projects now operate worldwide. However, for donors and funders who want to support these efforts, it can be hard to identify which organizations to trust with their money and even more difficult to determine which are effective.

“I would give talks, and people would ask, ‘Who should I donate my money to?'” Karen Holl, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) and reforestation expert, told Mongabay. “There was really no standardized way to answer that question.”

So how can a tree investor decide what organizations to support? What questions should ensure money goes toward the best outcomes for biodiversity, climate and people?

To help answer those questions, Holl and UCSC postdoctoral researcher Spencer Schubert spent more than a year evaluating “intermediary organizations,” the major groups that channel funding and resources to local tree-planting projects around the world.

Between October 2024 and June 2025, the team contacted more than 125 organizations. Seventy completed detailed surveys, while researchers performed systematic reviews of websites and public reports for the rest.

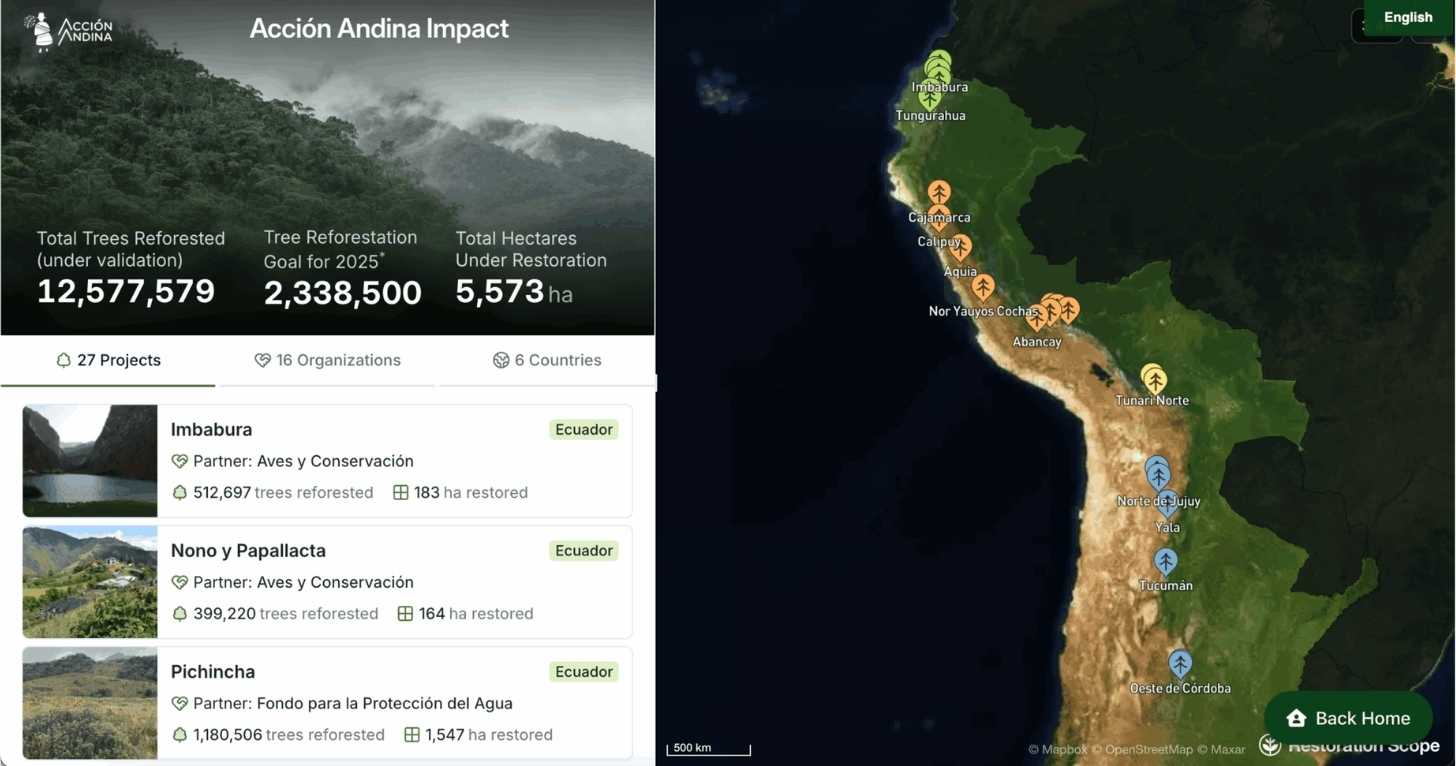

Mongabay has now launched this research as the Global Reforestation Organization Directory.

The directory was developed in collaboration with Mongabay, and the research was funded by the Center for Coastal Climate Resilience and the MacArthur Foundation Chair at the University of California Santa Cruz.

What this directory does (and doesn’t) do

The Global Reforestation Organization Directory provides standardized information about the public commitments and transparency of more than 125 major tree-planting organizations, making it easier for donors to compare groups and find the ones that match their priorities.

The directory doesn’t rank organizations or judge individual projects — it also does not recommend projects. Instead, it shows what organizations publicly share about following scientific best practices, avoiding common mistakes and monitoring their results.

“It’s not a rank ordering of groups,” Holl said. “It’s also not a rigorous third-party verification of projects. We did not go into the field and check projects.”

What it does provide is standardized information for comparison.

“We’re setting the norm of what the standards are,” Holl said. “Before this, nobody had the information to compare organizations.”

It’s important to note that this directory focuses on intermediary organizations that fund multiple initiatives, which differs from Mongabay’s existing Reforestation app database that documents individual tree-planting projects.

Since a single reforestation project can involve many different organizations working together, and projects from the same organization can look very different depending on where they are, it’s important for donors to have information about both the organizations and the individual projects.

Much of the project evaluation relies on the organization’s self-reporting through surveys or website statements. The researchers acknowledge this limitation but argue it still provides value.

“Many people use Charity Navigator, which is also based partially on self-reported data,” Holl said. “Our site is a place to start. Right now, nobody has any information.”

The researchers did verify some things, such as whether organizations’ monitoring protocols and financial reports actually exist online and the availability of public tree survival data. They also reviewed certification standards when relevant (such as Verra, Plan Vivo and The Global Biodiversity Standard).

Many organizations are collecting data, “but then there isn’t a follow-through on the public reporting side,” Schubert said. “There’s a disconnect.”

The absence of information on an organization’s website doesn’t necessarily mean the organization has neglected those criteria. Some excellent programs may lack the staff or resources to maintain public dashboards.

However, transparency signals that an organization understands the complexities involved in reforestation and has the capacity to organize, monitor, and report results.

As an investor, picking the right organization matters. Not all tree-planting efforts pack the same punch. And while increasing tree cover has many potential benefits, it can also have negative consequences, such as destroying diverse grasslands, introducing invasive species, and displacing deforestation into remnant forests.

Projects also have the potential to benefit or harm the communities they involve.

With this in mind, the researchers created an evaluation that assigns points across four categories: permanence, ecological, social, and financial, each backed by scientific literature on best practices.

The four tenets: Permanence, ecological, social, and financial

The first category, permanence, examines whether trees are surviving and tree cover is increasing over time. The category investigates whether organizations have standards in place for picking effective projects and if these projects actually address the causes of deforestation. Permanence also involves land tenure, as well as making sure organizations have strong maintenance and monitoring plans.

“We’ve graduated from asking, ‘How many trees did they plant?’ to ‘Has tree cover increased over time?'” Schubert said.

The second category, ecological, asks whether projects are planting the right trees in the right places. The category evaluates tree species selection (Are they native? Are they useful to communities?) and seed sources to ensure genetic diversity. It also asks whether organizations are monitoring changes in biodiversity, such as an increase in wildlife.

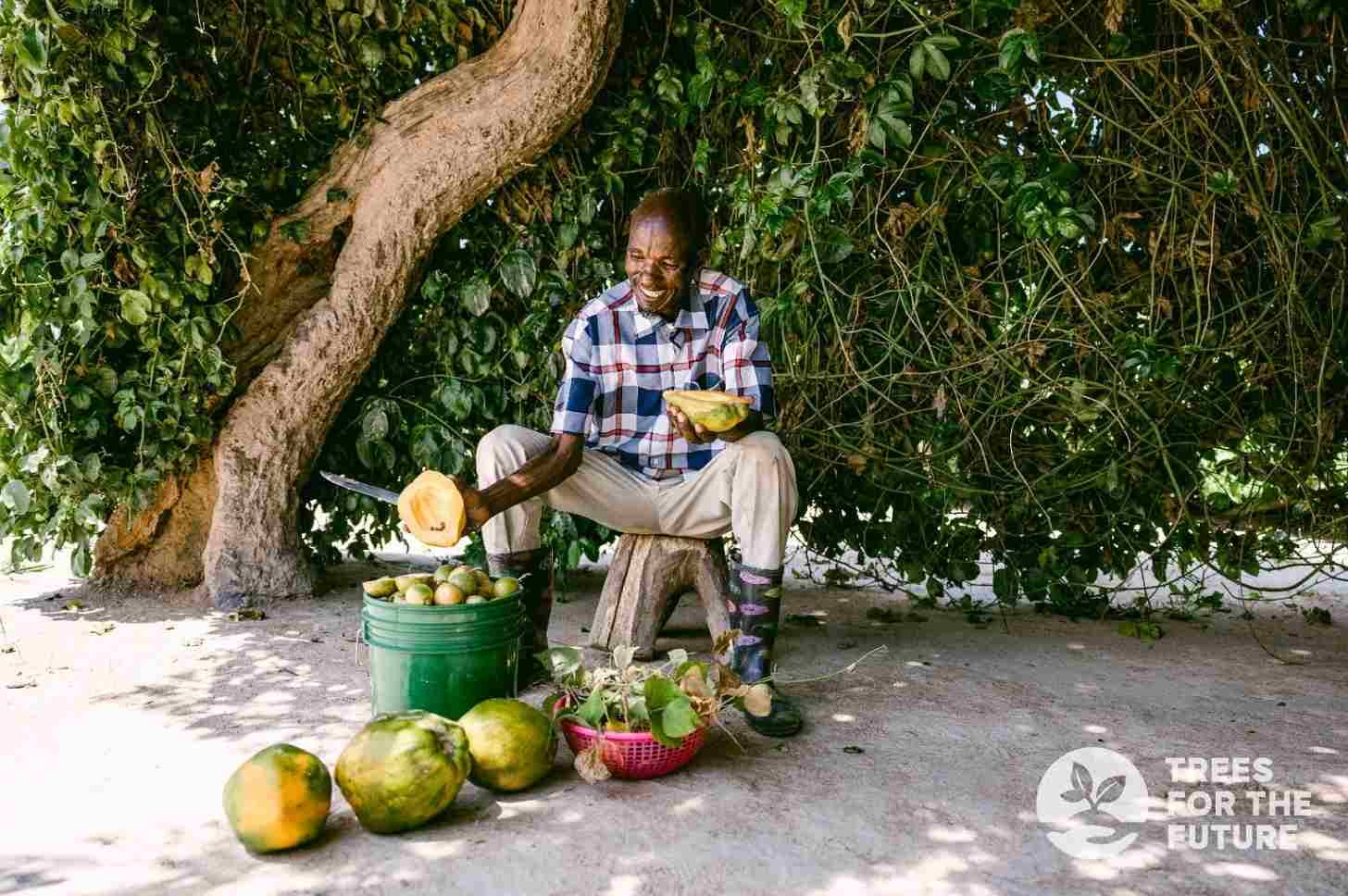

The third category, social, asks whether local people are benefiting from the project. This category assesses local community involvement throughout project phases. It looks at safeguards against displacing communities, support for landholders, and monitoring of benefits to local people, including gender demographics.

Finally, the fourth category, finances, looks at where the money is going. This category examines transparency around funding sources, disclosure of how much money goes to tree-planting organizations versus administrative costs, and whether there is long-term maintenance funding.

These four categories come from earlier research by Holl and Pedro Brancalion from the University of São Paulo, Brazil. They found that successful tree-planting projects share common features: secure land rights, genuine community involvement, plans for long-term care, and clear monitoring.

Their studies also showed that many organizations claim to follow best practices but don’t share enough details about their actual results. This gap between claims and transparency shaped how the directory evaluates organizations.

How to use the directory

The directory allows users to find organizations that align with their priorities.

For example, someone focused on carbon capture might prioritize organizations with strong public data on tree survival rates.

A donor concerned about community benefits might sort for organizations that score highly in the social category and search for organizations that require local involvement and track beneficiary demographics.

Someone interested in biodiversity conservation might look for organizations that plant only native species and monitor biodiversity indicators.

Each organization is displayed with a radial bar chart consisting of four concentric circles. The completeness of each circle indicates the score in each category: permanence, ecological, social, and financial. For example, an organization that scored 100% in ecological would have a complete circle for that category.

But the researchers caution against discounting organizations based solely on the scored criteria. Not all organizations work the same way. Some work in remote areas where certain social criteria don’t apply, while others tailor standards to local conditions rather than impose rigid requirements. These flexible approaches can sometimes be more effective than one-size-fits-all policies.

Real-world examples from Mongabay’s reporting

Mongabay has reported on more than 30 of these organizations’ on-the-ground projects. These articles are linked to organizational pages in the directory, providing journalistic context about how the projects funded by these groups actually operate.

For example, Mongabay’s coverage of the Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust in Malawi, funded by the intermediary organization WeForest, reveals the extreme dedication required for native species restoration, with workers hiking for hours to carry seedlings up the “Island in the Sky” to save the endangered Mulanje cedar (Widdringtonia whytei).

An article about search engine Ecosia shows how the company has evolved beyond simply funding tree planting to partnering with satellite monitoring startups to verify their carbon claims.

Reporting on forest garden projects in the Sahel illustrates both the promise of ancient agroforestry techniques and the challenges of scaling them across water-scarce regions.

Detailed Mongabay reporting adds depth beyond basic scores and data, helping donors understand not just what organizations say they do, but how their on-the ground work actually happens in real places with real challenges.

Moving forward with transparency

“Any organization can put up a website or make a video of their farmer saying, ‘This is wonderful,'” Holl said. “But what we were really pushing for is transparency of data. … If you’re going to say you’re doing this, then you need to show that you actually are.”

To organizations, Holl’s message is direct.

“What are your goals? And if those are your goals, what are measurable objectives, and how are you measuring them? You need to be clear about what you’re trying to achieve and honest about how well projects are meeting their targets.”

Organizations claiming to restore biodiversity should measure biodiversity, she said. Those focused on community livelihoods should track whether locals are benefitting from the projects.

By evaluating these organizations, “our goal was not to be punitive,” Holl said, “but to try to incentivize groups to follow best practices.”

Holl sees evidence that change is already underway. Organizations are improving their monitoring commitments compared with earlier research. But “actually monitoring and also making those data public,” she said, “those are the next steps.”

For now, the directory offers something previously unavailable: a systematic way to compare how major reforestation organizations approach the complex challenge of growing trees that survive, benefit communities, and support biodiversity for the long term.

Current funding for the project only supports directory updates through December 2025. The team is seeking additional resources to maintain the platform in the long term as organizations update their practices and new tree planters enter the field.

This article was originally published by Mongabay.

Header Image by Tree Aid