During a routine research dive off the coasts of Southern California and Alaska in 2021, Occidental College professor Shana Goffredi scoured the ocean floor looking for methane seeps — deep-sea spots where methane gas bubbles up from the Earth’s crust.

After scooping up samples 3,000 feet below the surface, Goffredi and her team took them back to the lab “just to see if there was anything unusual about them.”

That’s when they discovered three new species of deep-sea spiders.

In addition to living exclusively in methane seeps and hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, the Sericosura sea spiders displayed a curious behavior: They consumed methane gas.

“Sea spiders at hydrothermal vents and methane seeps are understudied,” Goffredi and her colleagues explained in the new study, which was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Sericosura sea spiders now join the likes of other overlooked, yet abundant, small marine animals that take advantage of methane.”

Goffredi, who specializes in the symbiosis between bacteria and invertebrates on the seafloor, was hungry to know more.

In 2023, the professor and her team of undergraduates returned to the ocean habitat with an underwater submersible. But at a centimeter long, the sea spiders were hard to spot.

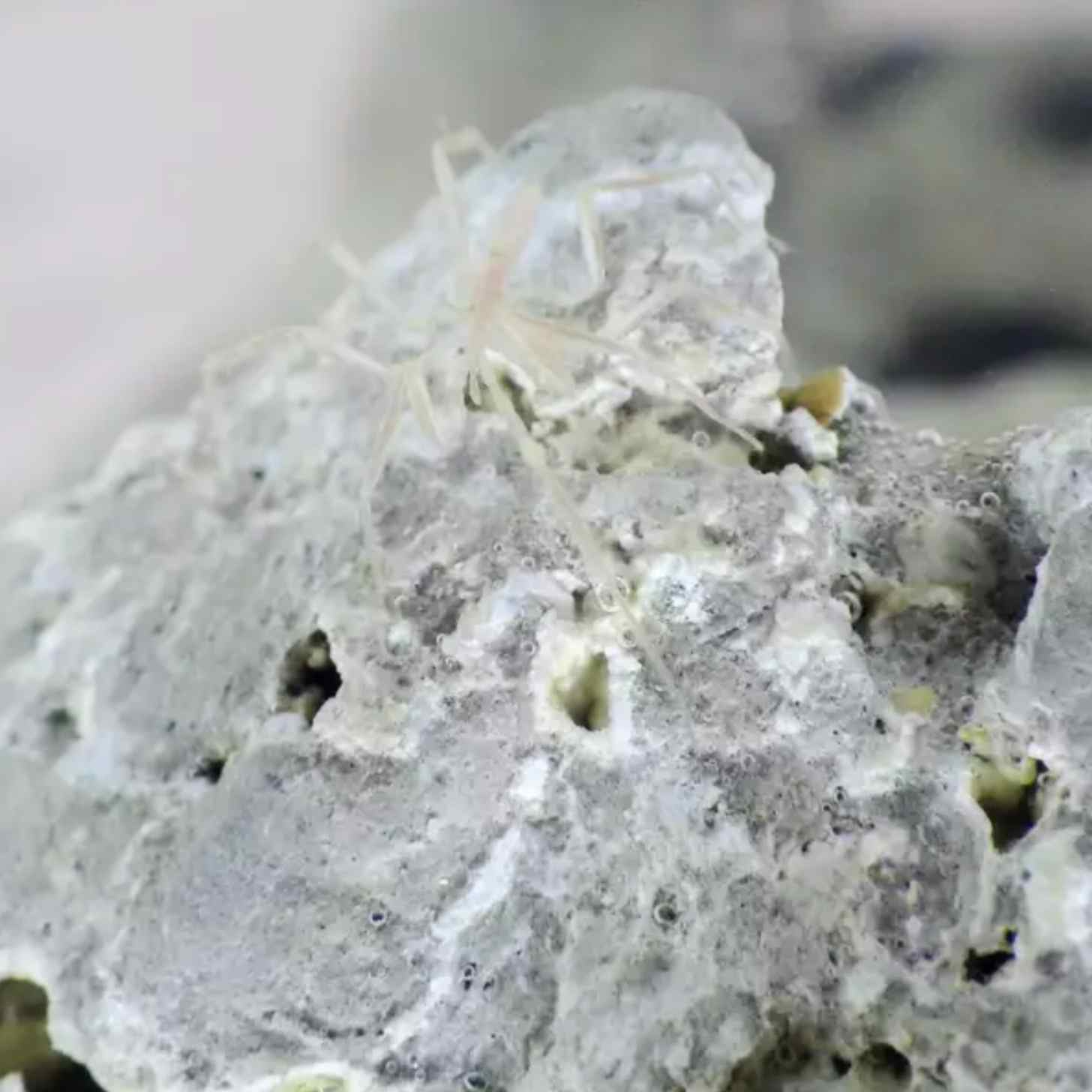

Especially because they were translucent.

“I came up out of the submersible all dejected because I thought we didn’t collect any,” Goffredi told SFGate. “And it turned out we’d collected over 30 of them.”

After securing more samples, the team confirmed a long-held hypothesis. Unlike other spiders — both deep sea and on land — these new species of Sericosura were physiologically unique.

They had “a coat of methane-oxidizing bacteria on their surface” which allowed them to collect methane on their exoskeletons.

“Methane has been recognized as a potentially important source of carbon and energy for lake food webs,” Goffredi and her colleagues wrote.

“In the case of sea spiders, however, they appear to cultivate and consume the methane-oxidizing bacterial community from their bodies directly, rather than from abiotic surfaces.”

Close-up pictures of the spiders, which have a set of “lips” fringed with fleshy bumps and three miniscule teeth, may serve as nightmare fuel for any unsuspecting arachnophobes who scroll past this latest ocean discovery.

Goffredi, however, finds them “extremely adorable.”

“While the deep sea feels far away, all organisms are interconnected, and the processes in one ecosystem affect the other,” Goffredi told SFGate.

Goffredi suspects that 11 other recently discovered deep-sea spiders may have “methane-sucking” tendencies, too.

As she looks forward to future expeditions, Goffredi concluded that the groundbreaking discovery “reveals a new biological conduit for methane input into ecosystems” and “expands our understanding of C1 compound cycling in the ocean.”

“The deep sea is so important. It’s involved in climate regulation, production of oxygen, and supply of fisheries,” Goffredi said.

“So it’s really important to understand the biodiversity of these unique places.”

Header image via Shana Goffredi

You may also like: A new animal with 200 legs was just discovered, and it's sucking up deep-sea trash