Toads can lay between 2,000 and 20,000 eggs in a season. But only one in 50 will typically survive the leap from egg to tadpole to "frog-hood."

“They lay those eggs, and they develop into teeny, tiny tadpoles, of which only a fraction ever make it out of the pond,” Dr. Mark D. Scherz, the curator of herpetology at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, told CNN.

On November 6, Scherz and his colleagues published a new study in the journal Vertebrate Zoology.

The research, which analyzed 257 specimens across five museum collections in Europe, discovered three new species of Nectophrynoides hiding in plain sight.

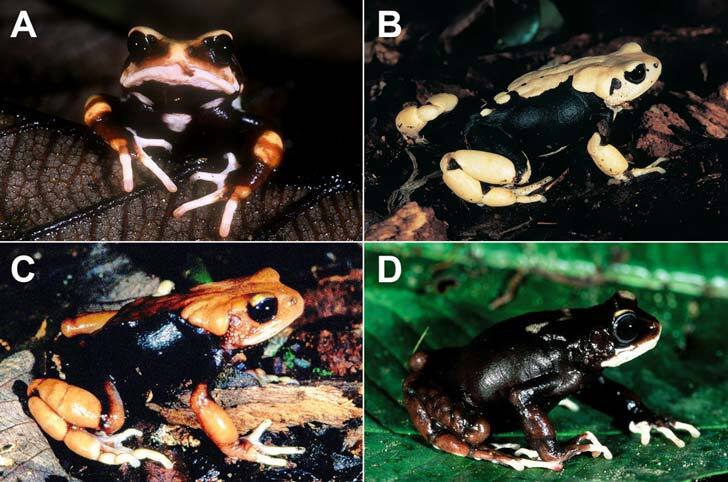

Since it was first discovered in Tanzania in 1926, the distinct, robust toads — which come in a variety of colors from white, yellow, gray, brown, red, and black — had all been mistaken for one species: Nectophrynoides viviparus.

Like others in the genus, the three new species (N. luhomeroensis, N. uhehe, and N. saliensis) have an unusual lifecycle.

Instead of laying eggs in ponds, the females fertilize their eggs internally and give birth to live “toadlets” — a process which skips the tadpole phase altogether.

The toad broods are much smaller than their egg clutch counterparts — around 40 or 60 toadlets instead of numbers in the thousands.

“The maximum we’ve ever recorded was, I believe, over 160 fully developed toadlets inside one individual,” Scherz said.

Still, the herpetologist estimates that those toadlets have a higher chance of surviving to adulthood.

When studying the museum specimens, some were more than 100 years old. Remarkably, several female toads still contained “large yolky eggs” and partially developed embryos that confirmed evidence of live toadlet births.

“There’s no question that this is now correctly assigned,” Scherz said. “It’s really a game changer.”

In their conclusion, the researchers invited further study of the many Nectophrynoides species at large, and how their most vulnerable populations have been affected by climate change and deforestation.

“Further surveys are needed to fully understand the distribution, ecology, and possible population trends in these areas to inform future conservation strategies,” the authors wrote.

Conservation ecologist Dr. Diego José Santana, who works as a curator of amphibians at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, said that this latest research was revelatory to his field.

“Describing these new species that give birth to live young is fascinating and helps us understand the evolutionary flexibility of amphibians, one of the most diverse and ecologically sensitive groups of vertebrates,” Santana told CNN.

“[This work] underscores the importance of continued investment in taxonomy and natural history collections,” he continued. “Working at the Field Museum, which holds specimens from all over the world, I’m constantly reminded that many new species are still waiting to be recognized.”

You may also like: Nature survey in tropical paradise leads to new species of 'diamond-eyed' toad

Header image via Judy Klimek (CC BY-SA 3.0)