The morning of June 25, 2025 — the day after the New York City Democratic mayoral primary — social media was abuzz.

Half of the people online, including President Donald Trump, were pointing fingers at now-Democratic mayoral nominee Zohran Mamdani and calling him a “Communist Lunatic.”

The other half had a different take.

“Congratulations to Zohran Mamdani on an historic victory … ” Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez posted on Instagram.

“It’s time we acknowledge that not all Democrats are the same. We’ve got people, they’ve got money.”

In another post, she shared a video in which she is embracing Mamdani on the streets of New York in a tight hug. It’s captioned: “A better world is possible.”

Mamdani is notably a candidate who targeted voters outside of his political party. He identifies as a democratic socialist, but in the months leading up to the primary, he visited Republican strongholds across N.Y.C., like Staten Island and Queens, where locals swung further right in the presidential race.

And he asked people why they voted the way they did.

“After the presidential election, we saw that New York was actually the state with the largest swing in the country toward Donald Trump, and that swing took place far from the caricature of Trump voters and instead taking place in the hearts of immigrant New York City,” Mamdani said in an interview the day after the primary election.

“I went to those neighborhoods. … Again and again, what I heard from them was cost of living, an inability to afford the very things they recalled being able to purchase four years ago. Again and again, they asked for a relentless focus on an economic agenda. Ultimately, in listening to them, we built a campaign that was explicitly about making this city affordable.”

He says he discovered that the people who voted for Trump were desperate for a more affordable life. So, he took an uncommon approach, which he calls “listening instead of lecturing.”

“Too often in politics there’s a desire to impose what you think the debate is on the people you seek to represent,” he continued, “as opposed to listening to the very issues that are making it difficult for them to keep calling the city that they love the city that they live in.”

The Mamdani Effect

This approach is something Amanda Litman, the CEO and founder of Run For Something, is seeing across the country.

Run For Something is a political organization founded on Trump’s first Inauguration Day in 2017 that “recruits and supports young, diverse progressives to run for down-ballot races.”

In her new book, “When We’re in Charge: The Next Generation’s Guide to Leadership,” Litman posits: People are looking for the leaders of the future, and they won’t look or act like the ones we have now.

People are looking for the leaders of the future, and they won’t look or act like the ones we have now.

“I think the things that made Mamdani so effective here were that he ran values first, voters first, showed up where people are, [and] understood that social media is not an afterthought,” Litman told Good Good Good.

“Like, yes, Zohran Mamdani could only win in New York City. But a values-driven, voter-first candidate who knows how to communicate where his, her, or their neighbors are, can win anywhere.”

Leading up to and after the presidential race between Kamala Harris and Trump, Americans were disillusioned by electoral politics.

Or, at least, the politics of the past.

As early as 2023, Gallup polling showed that younger voters are rejecting political parties, with 52% of millennials and Gen Z registered as independents, compared with only one-third of Baby Boomers.

The same age group — millennials and Gen Z — also polled as the least likely age groups to vote in the 2024 general election.

“Respondents who do not think they will vote said it was because they feel like their vote doesn’t matter, they don’t like any of the candidates, and the candidates do not represent their political beliefs and ideas,” a summary of the poll explained.

A more recent June 2025 Pew Research Center survey found that 62% of Americans say they are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in the country, compared to just 37% who are satisfied.

But Litman says a new generation of candidates is alchemizing this disappointment and disillusionment into a real opportunity to lead.

"As much as people were inspired by grief and fury, they can be inspired by hope and opportunity. That this is the beginning of a change that we desperately need.”

In fact, in the week following Mamdani’s primary win, Run For Something saw a total of 10,000 people reach out and express interest in running for local office.

“One of the things I was really inspired by was that in the two weeks after the 2024 [presidential] election, we had about 10,000 people sign up to run. The only moment that has matched that is the 10,000 people who signed up to run in the two weeks after Mamdani won the mayoral race,” Litman told Good Good Good.

“For me, what that says is that as much as people were inspired by grief and fury, they can be inspired by hope and opportunity. That this is the beginning of a change that we desperately need.”

She elaborated: “We need new leaders top to bottom. Trump is the last of an old generation — both literally and figuratively — of people who are clinging to power. He is the end of the line. And we get a chance to actually make that true.”

While Run For Something does specifically promote progressive values, reduced civic engagement and participation impacts nearly all Americans, especially on a local level, with turnout hovering under 40% in most local elections nationwide.

Since its founding in 2017, Run For Something has recruited over 100,000 people to run for state and local office in all 50 states, with over 1,500 winning their elections.

The organization provides tools for those looking to run, including mentors, volunteers, funding, training, and a community of candidates who share similar experiences and support.

Litman’s goal is to get young, diverse people over the hurdles that have traditionally been impassable in politics.

“Most of the folks signing up to run with us are 40 or younger. About half identify as women, about half as people of color, a large rate of whom actually get on the ballot. They are running for things like school board, state house, state senate, city council, mayor, library board, water commissioner — the building blocks of democracy,” she explained.

This year, she said, many of the organization’s candidates are running on issues like affordable housing, childcare, transportation, and healthcare.

She believes that, with an approach similar to Mamdani’s, change is on its way.

“Run For Something has helped elect more than 1,500 people, including in Nebraska, and Kansas, and Iowa, and Alaska, who have brought their own lived experience and reflecting the values of the community they’re in,” she said.

“I’m not saying we need 10,000 superstar, charismatic, once-in-a-generation political talents. What we do need is 10,000 more people who really understand what their neighbors care about and give very specific ideas for how to solve things for them. That’s replicable anywhere.”

A New Generation of Political Talent

Kat Abughazaleh is trying to make a similar splash in the Ninth Congressional District of Illinois. Abughazaleh isn’t affiliated with Run For Something, but she is among the next generation of leaders trying something new.

The researcher and journalist — who has been the subject of Elon Musk’s ire in the past — is running to fill the seat of 80-year-old Rep. Jan Schakowsky, who has held the title since 1999, the year Abughazaleh was born.

Rep. Schakowsky will not seek reelection, but Abughazaleh called for others to run, hoping to participate in the “first competitive Democratic primary in the District since 1998.”

“I have a vision of how I think politics should be, and it’s not predatory,” Abughazaleh told Good Good Good.

“It’s pragmatic but positive. It’s person-to-person communication and collaboration, not stuff hidden behind paywalls or access hidden behind high income. I said, ‘Screw it. I believe in competitive primaries. Let’s run.’”

“I have a vision of how I think politics should be, and it’s not predatory."

A big part of her campaign efforts are, yes, to speak up on the issues — on her website she lists “anti-authoritarianism,” climate change, reproductive healthcare, corporate consolidation, and “basic existence” as some of her key values — but it’s also to use the funds she’s raising to help her would-be constituents right now.

“In 2024, I was genuinely sickened at how much money went into that race just to lose. I thought about how many clinics could be funded, how many food banks could be stocked, how many people’s tuition could be paid for — and it just wasn’t,” she said. “So I thought, ‘Hey, what if we did actions?’ and I’m trying to lead by example on that.”

She has hosted food drives, menstrual product drives, craft events, and community cleanups out of her campaign headquarters. People are invited to stop by and grab anything they might need, from clothes and school supplies to food, condoms, or Narcan.

“All of our events are packed. I’d say half of them are people that have never even been politically involved besides voting before,” Abughazaleh said. “I think everyone cares. It’s just a matter of if they feel like they have any power in their vote or in their actions.”

She said making it fun and enticing — hosting punk bands and embroidery workshops from her offices, for example — is one way to show people you care. The other is to meet their material needs and prove that you’re willing to show up for them.

She’s not banking on that being enough to earn her a vote, but so far, things have been looking good.

As of the publication of this story, Abughazaleh’s campaign has onboarded over 5,000 volunteers and brought in 22,000 individual donations, totaling $1 million. The average donation is just under $32.

“You don’t have to vote for me. I’m going to help you either way. I am not going to yell at you. I’m just going to say you deserve housing, groceries, and health care with money left over to save and spend,” she said.

“Every single person deserves that. And when people’s material needs are met, they’re able to enjoy more of life, be more politically involved, pursue their passions, education — so many things that our system is inherently built to discourage.”

Underneath it all, Abughazaleh is very transparent about how difficult it’s been to run, as someone with little financial backing or lobbying interests.

“I’m just functioning on savings. We’ll probably go into debt. My only income is a Patreon where people send me a dollar to look at pictures of my cat,” she said.

But in addition to winning, her motives are clear: “I want to raise the bar for what public service should be, specifically in elected positions.”

Other candidates who are involved with Run for Something have taken similarly fun, more personal approaches to community engagement during their campaigns.

Lily Franklin, who is running for a seat on Virginia’s House of Delegates, is a teacher and dog mom. She has a specific sect of supporters who are students at Virginia Tech — Students Vote For Lily.

Franklin’s dog, Poppy, is also incorporated in her logo and serves as the face of a social media series called Poppy’s Policies, in which a silly voiceover breaks down policy ideas to reduce housing costs, support underfunded schools, and more.

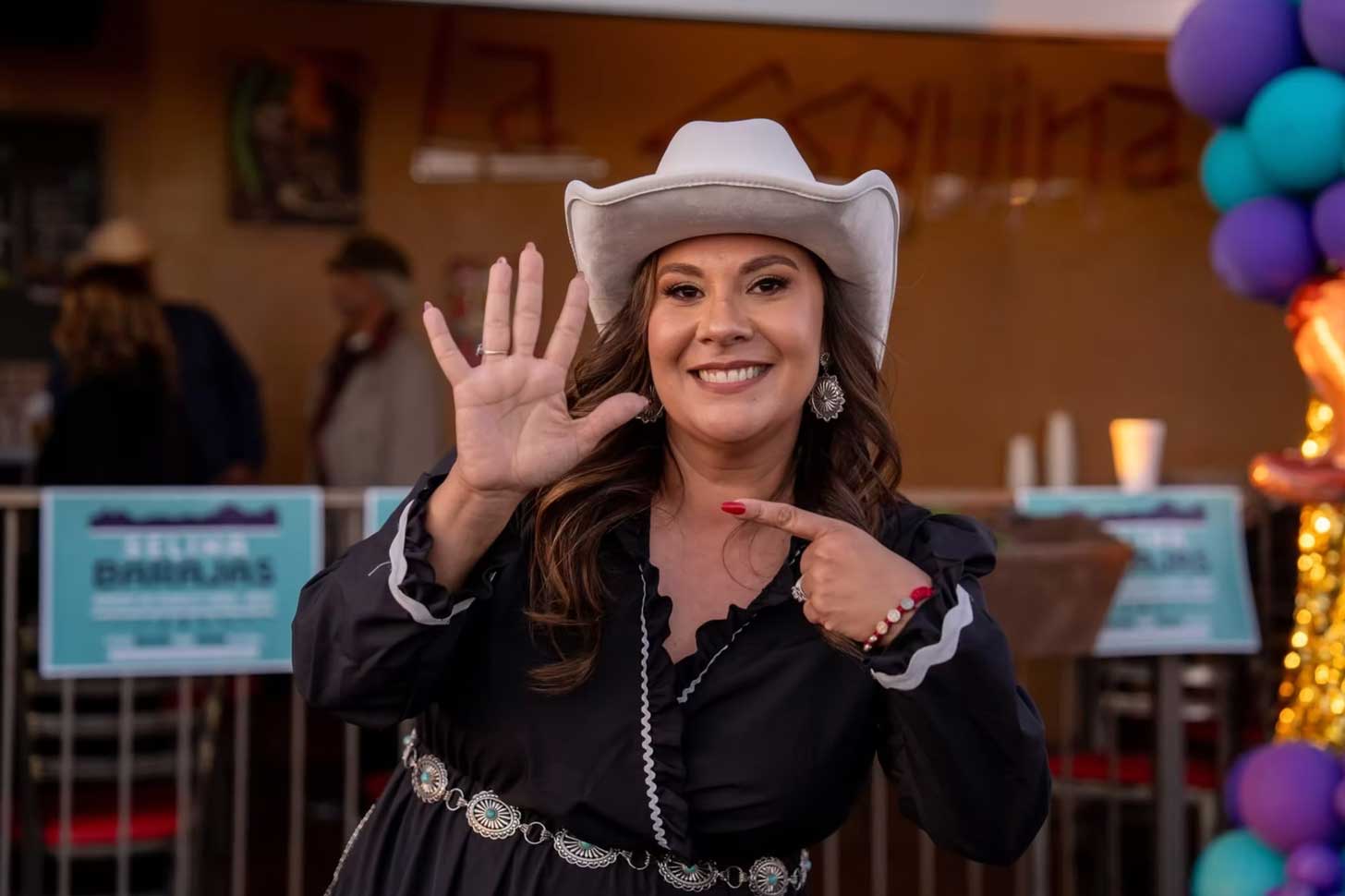

Selina Barajas, a candidate for Tucson, Arizona’s city council, has downloadable coloring sheets for her supporters to enjoy and display. She just won her primary.

Jayden Williams, who is running to be mayor of Stockbridge, Georgia, gleefully hosted a line dancing party to fundraise for his campaign and earn votes this summer.

And Kelsea Bond, a non-binary community organizer running for Atlanta City Council, has an Instagram page full of activities any 20-something would be eager to attend.

Supporters can join a flash tattoo fundraiser, “sipping tea with Kelsea” socials, and even cash in on an idea straight out of the Mamdani playbook: Campaign canvassing punch cards for volunteers to trade in for a prize after they have volunteered 10 times.

Power in Community

At the end of the day, what these candidates have in common is not necessarily their political aspirations or organizing tactics, but a deep and unwavering commitment to building communities and movements that last — and not just until the 2026 midterms.

“We can’t just win a majority. We have to make sure a majority of that majority wants to make actual change,” Abughazaleh said. “That means making running for office more accessible. It means encouraging competitive primaries. It means … ensuring that campaigns aren’t just about money.”

For Litman, the inspiration isn’t just the potential of these candidates winning, but that they decided to step up and run in the first place.

“Everyday, hundreds — if not thousands — of people are saying, ‘Yeah, maybe I’m going to run for office.' The bravery, both emotionally, but also in some cases, physically … I am just so in awe of these folks, and I think they’re doing something so meaningful,” Litman said.

“You don’t run for office because you hate where you live. You run for office because you love it, and you want to make it better. I think that is so powerful, and I find that really inspiring. I’m really grateful that Run For Something gets to be part of that.”

And you don’t have to be a decades-long political strategist to be inspired by that, either.

“I think what gives me hope is all the people I talk to every day are volunteers who chip in because they want to help out because they want to help others,” Abughazaleh continued.

“It’s the two unhoused ladies that come to our office and get what they need and then grab some literature to disperse among their friends. It’s the dad that brought his kids in, and then they took a sticker and the son put it on his tricycle. It’s the couple that comes in with their cat in a backpack because they know I want to see their cat. It’s all of these things. You know, as Mister Rogers said, look for the helpers.”

For Mamdani, the helpers in his eyes are the coalition of volunteers and supporters that will carry him to the general election this fall.

“This volunteer team that we’ve built, of now more than 50,000 people, they are the New Yorkers for whom democracy had started to lose meaning, had started to lose its relevance to the struggle of everyday New Yorkers,” he told Jen Psaki in an interview.

“They are the ones who, for so long, had not seen themselves in our local politics. But they are also the ones who brought us to this point.”

While the 2026 midterms are the hot topic of the day, Litman said the fight for the future is already well underway.

“Everyday, hundreds — if not thousands — of people are saying, ‘Yeah, maybe I’m going to run for office.'"

“2026 is going to be a really big opportunity. There are going to be very high odds against us in many of these places,” Litman said. “We know the other side does everything they can to make it feel impossible for us to win. It is not.”

Her advice is simple: Find your role and fill it.

“If you’re not the right person to run, ask a friend to run. Find the best person. Be the recruiter you wish to see in the world. Get involved in these local elections,” Litman said.

“The mantra I keep coming back to is: the way that we did things yesterday does not dictate the way we do things tomorrow. We have agency, and we can decide what we do with it.”

Header image by Good Good Good, with photos courtesy of Lily Franklin, Kat Abughazaleh, Zohran Mamdani, Jayden Williams, and Kelsea Bond