After water, concrete is the second most widely used material on the planet. Modern concrete, called Portland cement, has been in use since the late 1890s, but it’s gone through many iterations to get to this point, from the hydraulic lime mixtures of Nabataea traders in 6500 BCE to the gypsum and lime mortars used to bind the Egyptian pyramids.

Now, engineers are finding inspiration by looking back at one of the most prolific eras in concrete’s long history: Ancient Roman architecture.

By mixing volcanic ash, lime, and seawater for their cement mixtures, the Romans created grand structures that have withstood centuries of earthquakes, fires, and floods.

On July 30, a team of international researchers explored the potential use cases of returning to Roman concrete for construction materials.

“The remarkable longevity of Roman concrete has long fascinated researchers and hinted at its potential as a sustainable alternative to modern concrete formulations,” observed lead author Daniela Martinez and her peers in the study, which was published in the journal iScience.

“However, rigorous assessment of its environmental impact — particularly in the context of modern production technologies — has been lacking.”

“Here, we follow the life cycle assessment methodology to systematically quantify the impacts of various Roman concrete formulations relative to modern technologies.”

In a statement, Martinez said that she and her colleagues were drawn to the subject as a way of weighing the environmental impact of modern concrete versus ancient concrete.

“Studying Roman concrete can teach us how to use materials in a way that can maximize the longevity of our structures, because sustainability goes [hand-in-hand] with durability,” said Martinez, who works as an engineer at the University of the North in Barranquilla, Colombia.

“We were interested in how we can draw lessons from their methods to inform some of the climate-mitigation challenges that we currently face in our built environment.”

Initially, the “ancient recipe” for concrete would require more energy and water to produce.

The trade-off, Martinez said, is longer durability.

“When we take concrete's service life into consideration, that's when we start seeing benefits,” Martinez said, pointing to high-use applications like roads and highways.

“In cases where prolonging the use of concrete can reduce the need to manufacture new materials, more durable concrete has the potential to reduce environmental impact,” agreed co-author and engineer Sabbie Miller of the University of California, Davis.

Modern concrete is often reinforced by steel, which is subject to rusting and expanding over time. With that expansion, cracks can form, causing significant deterioration in as little as 10 years.

Roman concrete, however, is “self-healing” — when cracks appear, the lime fragments within the concrete react with water, creating a natural glue that repairs damage over time.

Hence why the Colosseum and the Pantheon are still standing, nearly 2,000 years later.

In their conclusion, the researchers invited “continued research and innovation,” which are essential to “harness both the historical wisdom of the ancient Romans and contemporary solutions in creating a more sustainable built environment.”

“There's a lot of lessons that we can draw from the Romans,” Martinez said. “If we can incorporate their strategies with our modern innovative ideas, we can create a more sustainable built environment.”

You may also like: Giant, ancient crabs live beneath Rome, and conservationists have their backs: 'They deserve to be saved'

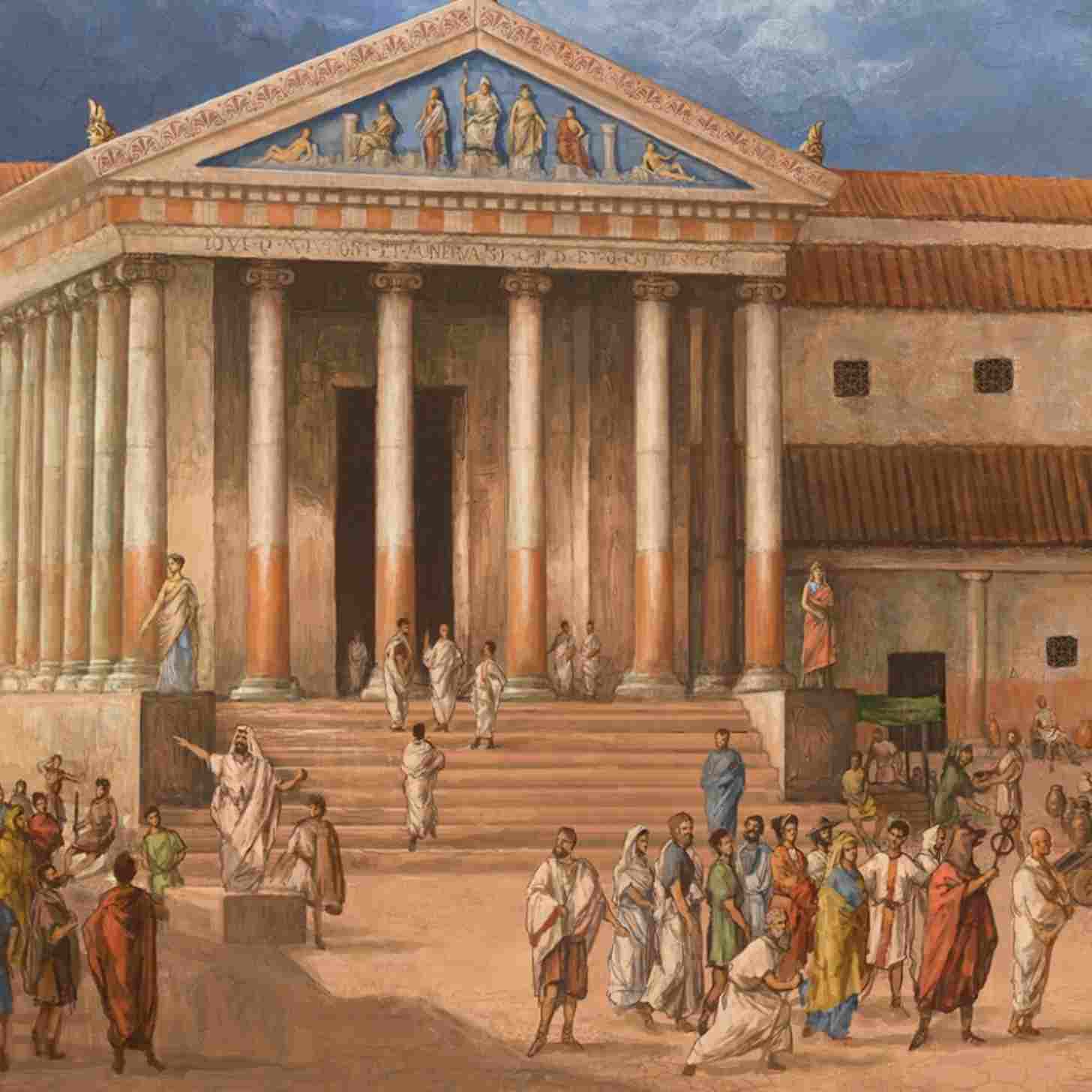

Header image via Diliff (CC BY-SA 2.5)