Thirty previously unknown deep-sea species — including a carnivorous “death-ball” sponge — have been confirmed in the depths of one of the most remote regions on the planet, thanks to new research from The Nippon Foundation–Nekton Ocean Census and its collaborators.

These discoveries, published on October 29, stem from two 2025 research cruises conducted with the Schmidt Ocean Institute and were verified during the Southern Ocean Species Discovery Workshop, hosted by Universidad de Magallanes in Punta Arenas, Chile, in August.

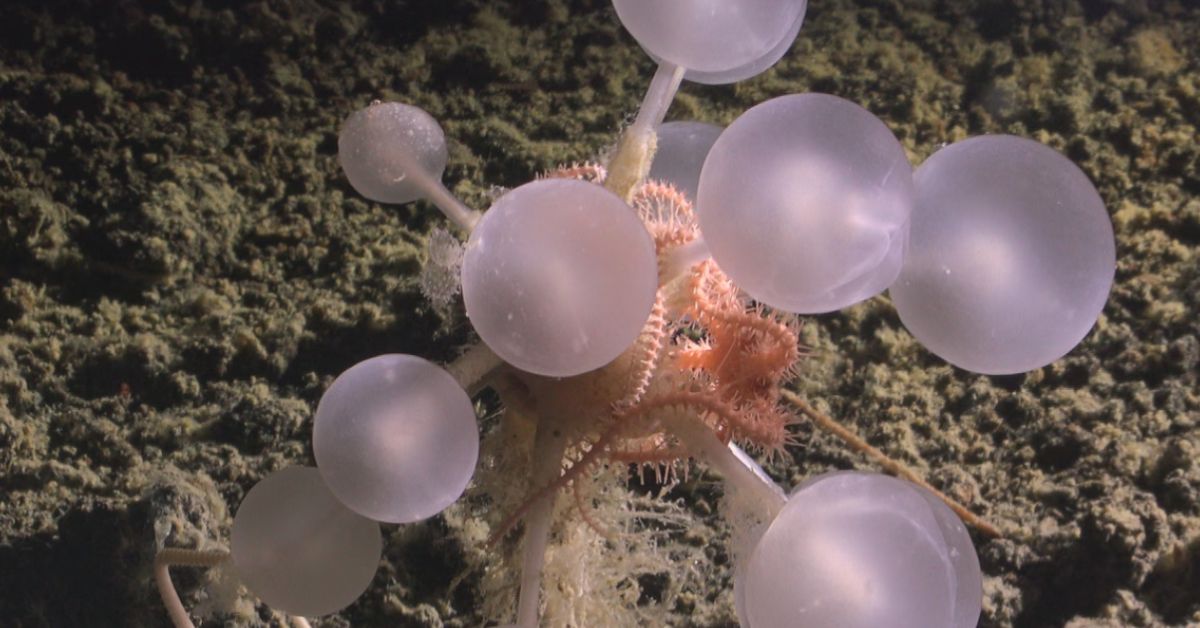

The leading discovery of the predatory “death-ball” sponge was particularly exciting to marine scientists.

Unlike most sponges that feed passively by filtering water, this species uses minuscule hooks across its spherical body to ensnare its prey.

“Advanced tools — from precise seafloor mapping to high-definition ROV imagery — allow us to explore and gather data from places never seen before by humans,” said Dr. Jyotika Virmani, the executive director of the Schmidt Ocean Institute.

“The goal we share with Ocean Census to accelerate discoveries has resulted in the first confirmed sighting of a juvenile colossal squid and new species, and exemplifies what becomes possible when technology, ship time, and a global science network work as one.”

The Southern Ocean expeditions uncovered dozens of new species, including new types of black corals, armored and iridescent scale worms, new sea stars, and new crustaceans such as isopods and amphipods — some of which may constitute a new amphipod family currently under review.

The expeditions also led to the discovery of a new type of sea pen (a pink deep-sea animal that resembles a feather quill), rare gastropods and bivalves specially adapted to volcanic and hydrothermal environments.

They also found zombie worms — extremely rare deep-sea worms with no mouth or gut that use symbiotic bacteria to break down fats inside the bones of large vertebrates, like deceased whales.

Dr. Michelle Taylor, the head of science at The Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census, said the Southern Ocean remains “profoundly under-sampled.”

“To date, we have only assessed under 30% of the samples collected from this expedition, so confirming 30 new species already shows how much biodiversity is still undocumented,” said Taylor, who also teaches as a senior lecturer at the University of Essex.

“By coupling expeditions with species discovery workshops, we compress what often takes more than a decade into a faster pathway while maintaining scientific rigour by having world experts involved.”

During the Southern Ocean Species Discovery Workshop, an international team of taxonomists expedited species verification by sorting, imaging, and comparing specimens on site, using targeted DNA barcoding when required.

This ocean-to-lab workflow allows scientists to fast-track new species descriptions and add them to the taxonomic record — a process that historically takes an average of 13.5 years to complete.

Taylor, who is one of the world’s leading experts on deep-sea corals, emphasized the importance of Ocean Census.

“This is exactly why the Ocean Census exists — accelerating the discovery of ocean life and making it openly available,” she said.

“Each confirmed species is a building block for conservation, biodiversity studies, and untold future scientific endeavors.”

Through its accelerated species discovery model, the Ocean Census generates open, high-quality biodiversity data that support taxonomy, conservation planning, and ongoing research at a time when the ecosystem is rapidly adjusting to rising sea levels and rising global temperatures.

All validated records meeting the Ocean Census ‘Discovered’ criteria will be archived in the open-access Ocean Census Biodiversity Data Platform.

You may also like: Scientists discover new creature with 'orange and black' coloring, agree conservation plan 'is urgently needed'

Header image via The Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census/Schmidt Ocean Institute