Luiz Rocha has always dreamed of being an explorer.

“I had aquaria starting from age 5 or 6,” said Rocha. “And I decided to be a biologist when my third-grade science teacher brought in fish for a class. I’ve just always had this attraction to fish and going out in the ocean.”

Today, as the ichthyology curator for the California Academy of Sciences, Rocha has fulfilled his childhood dreams. Whether he’s boating on the open water or studying fish on a cellular level in the lab, the biologist has tackled some of his field’s biggest questions.

Rocha told National Geographic that there’s “nothing better for an explorer than going to a place that nobody has ever been, finding a species that nobody has ever seen before.”

And now, by venturing into the ocean’s twilight zone — the watery depths between 180 and 330 feet deep — Rocha’s latest expedition led to the collection of 2,000 specimens.

Remarkably, 100 had never been recorded in the region, and 20 were entirely new to science.

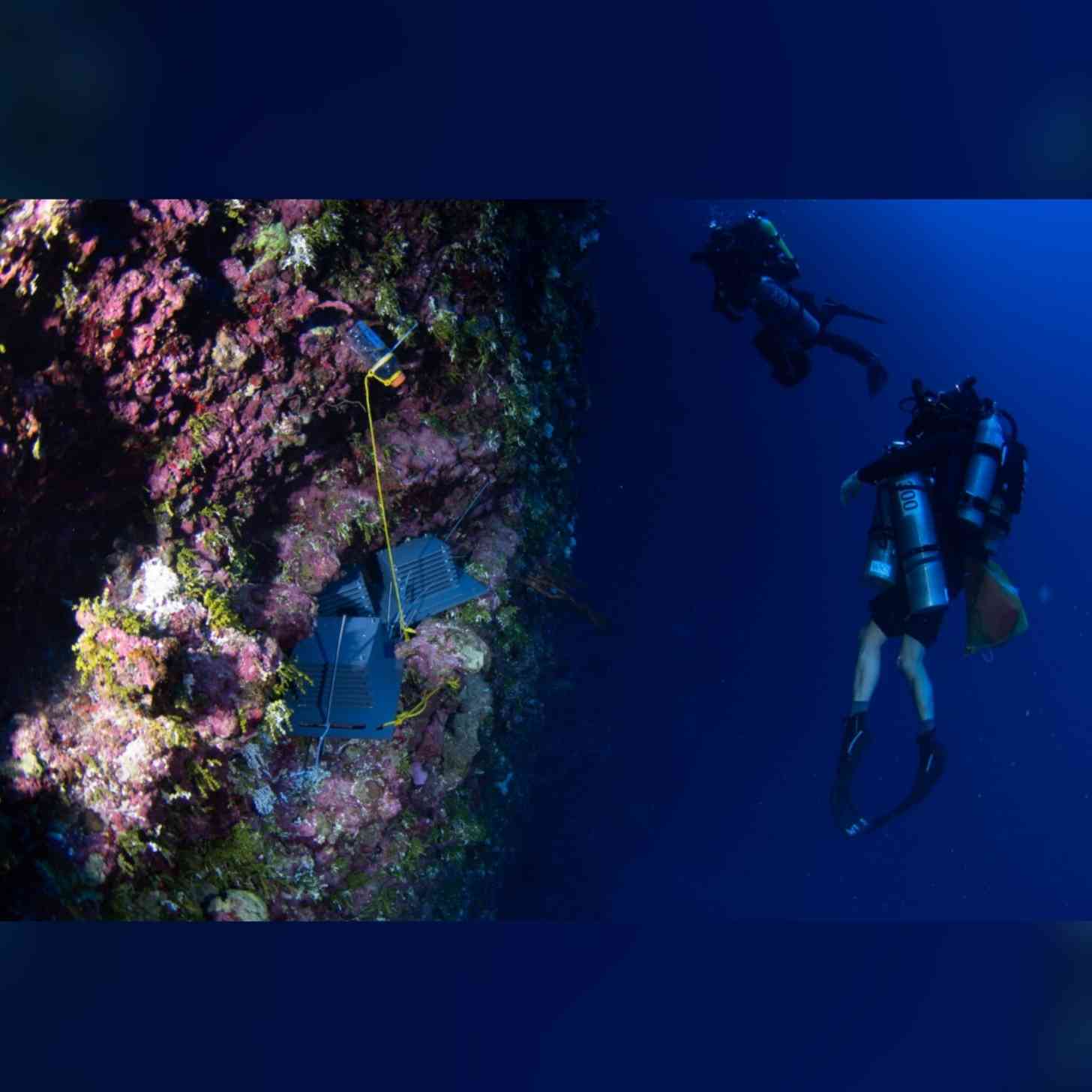

Rocha said that the expedition centered on the retrieval of autonomous reef monitoring structures, or ARMS, in Guam.

“[They] are essentially small underwater hotels that coral reef organisms colonize over time,” Rocha explained.

Some of the new species included a goby fish with a visible skeleton, a yellow-dotted sea slug, an orange cardinalfish, and a baby octopus marked with polka dots.

In an email interview with Forbes, Rocha emphasized just how monumental the Guam expedition was.

“As deep-reef scientists, our biggest limitation in studying the mesophotic zone is time, due to the long decompression needed to ascend,” he wrote. “While we humans can only spend 15-25 minutes surveying at these depths, ARMS have been collecting data 24/7 for eight years.”

“This long-term snapshot of deep reef biodiversity is unparalleled, revealing everything from never-before-seen species to evidence of a clear and steady warming trend at depth,” he continued.

“Understanding twilight zone ecology, connectivity, and vulnerability is essential for effective conservation planning in a rapidly changing ocean.”

Robert Lasley Jr., a curator at the University of Guam who specializes in crab diversity and evolution, said that this latest tactic for monitoring sea life “captures a remarkable diversity of marine life that cannot be obtained any other way.”

“Two weeks of processing the ARMS plates yielded more data and species records than we’ve ever seen before in Guam at these depths,” Lasley said. “Our findings highlight the complexity and richness of mesophotic ecosystems and underscore their need for protection.”

When Rocha and his team took the plunge in November, it marked the start of a two-year effort to retrieve 76 ARMS from deep Pacific reef, meaning countless discoveries have yet to be unpacked.

For Rocha, it’s just the beginning. He once told the California Academy of Sciences that the process of discovering and describing new species presents an ever-evolving puzzle.

“There’s been a lot of resurrecting names, or negatively validating names, or outright describing animals as new species. It’s a sort of Wild West of correcting and reclassifying things that continuously changes and advances what we know,” he said with a laugh. “It’s incredibly exciting.”

You may also like: 16,000 new species are discovered every year. Experts say discovery 'far outpaces the rate of species extinctions'

Header image via the California Academy of Science