You certainly don’t have to be a snowman named Olaf to like a warm hug. In fact, a recent study from researchers at Queen Mary University of London has found why exactly those hugs feel so good.

It has a lot to do with temperature.

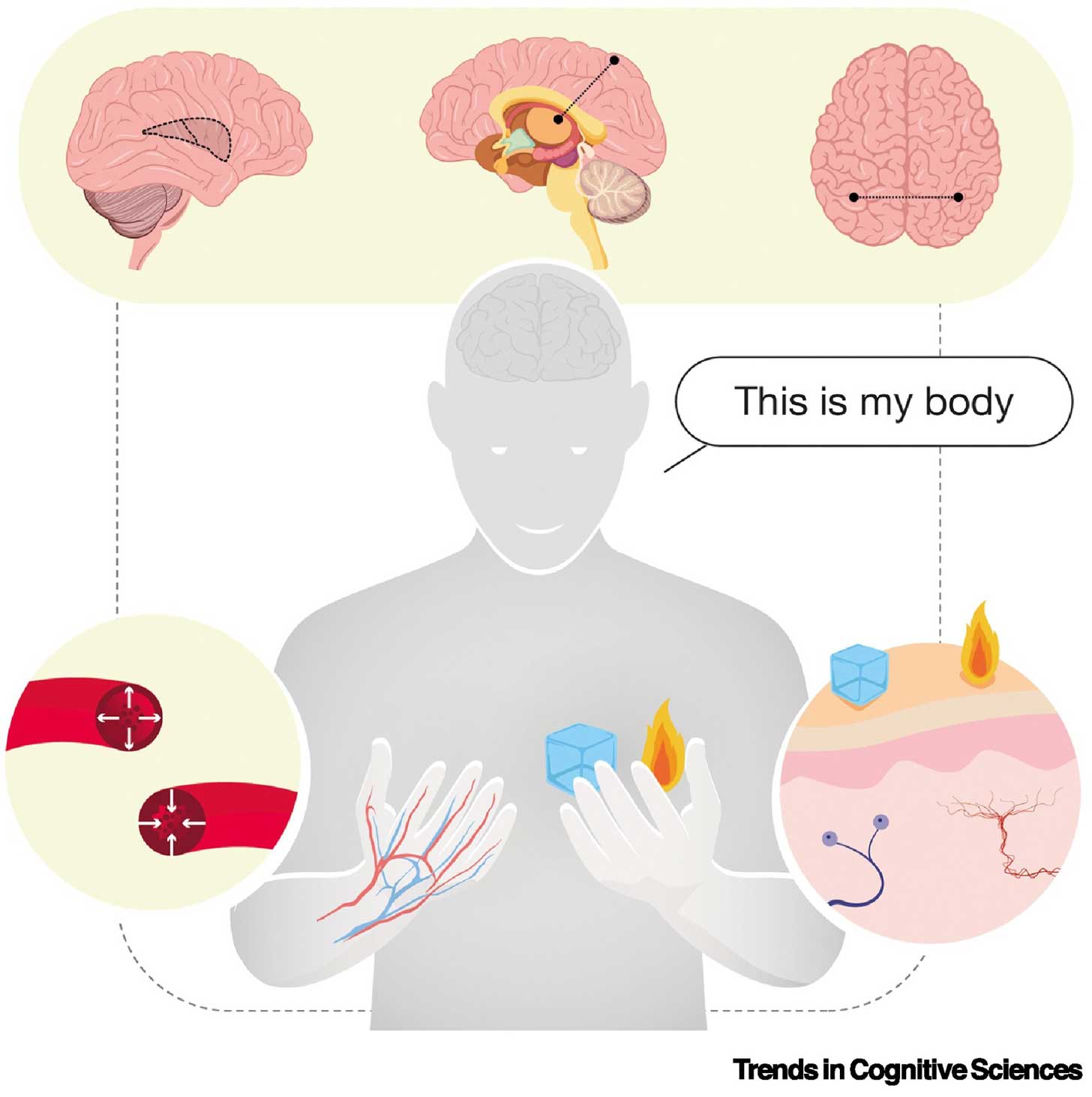

For most of academic history, temperature has been seen purely as a physiological signal, but researchers Dr. Laura Crucianelli and Dr. Gerardo Salvato wanted to dive into “thermoception,” or our perception of changes in skin temperature and how those changes influence how strongly we experience our bodies as “our own.”

There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that temperature changes how we feel in our bodies; think of your flushed cheeks on a cold winter day or the tingly feeling you get after warming up after being outside in the snow.

Crucianelli and Salvato’s latest research, published in the journal “Trends in Cognitive Sciences,” reviews decades of research in neuroscience, psychology, and clinical science to expand the understanding of bodily self-awareness to include temperature.

This work reveals a “previously overlooked pathway through which the body communicates with the brain,” a press release from Queen Mary University stated.

“Temperature is one of our most ancient senses,” Dr. Crucianelli also said in the press release.

“Warmth is one of the earliest signals of protection — we feel it in the womb, in early caregiving, and whenever someone holds us close. It keeps us alive, but it also helps us feel like ourselves. By studying how the brain interprets warmth and cold, we can begin to understand how the body shapes the mind.”

Researchers know that altered bodily awareness is present among many mental health conditions, like eating disorders, depression, anxiety, and trauma-related conditions. People might feel a sense of detachment, disconnection, or dysphoria in their bodies.

The scientists went into their research wondering if disruptions in temperature or perception of temperature may also accompany disturbances in “body ownership.”

“For example, we now know from experimental studies that thermal signals play a fundamental role in clinical conditions,” Dr. Salvato said.

“People with altered temperature regulation and temperature perception, due to a brain stroke, may develop pathological conditions according to which they do not recognize part of their bodies as belonging to themselves”.

The connection of thermal signals and the “skin-to-brain” dialogue, therefore, also contributes to possible sensory-focused interventions for mental health.

In addition to somatic psychology, this research also unlocks the potential for sensory rehabilitation among neurological patients, and may even inform the design of prosthetics that feel more natural.

And when it comes to everyday mental health maintenance, a nice, long hug really could have a major impact.

“When we hug, the combination of tactile and thermal signals increases our sense of body ownership, so we are more connected to our embodied sense of self,” Dr Crucianelli explained.

“Feeling warm touch on the skin enhances our ability to sense ourselves from the inside and recognize our own existence. We feel, ‘this is my body, and I am grounded in it.’”

Scientifically, warm interpersonal contact engages thermosensitive pathways that facilitate brain activity associated with safety and affective regulation. Combined with oxytocin release and reductions in stress, hugs support social bonding and enhance our connection to our bodies.

“Warm touch reminds us that we are connected, valued, and part of a social world,” Dr. Crucianelli concluded.

“Humans are wired for social closeness, and hugs briefly dissolve the boundary between ‘self’ and ‘other.’”

You may also like: How are we going to survive 2026? Here's what 3 therapists recommend

Header image by Ivan S via Pexels