In 2014, British wildlife photographer Margot Raggett was on a safari in Northern Kenya when she came across a poached elephant. The emotional encounter spurred her to action, and she began asking fellow wildlife photographers if they would like to contribute to a photo series in the name of elephant conservation.

“At the time, I was spending a lot of time out in the field in Kenya, so I was meeting a lot of wildlife photographers,” Raggett told Bob Books.

“So I started asking the photographers I knew if they would contribute an image or two towards a book to raise money for elephants. Everyone I asked said yes, and then I would ask them if they knew any other photographers they could introduce me to.”

In the end, 65 photographers — including National Geographic collaborators Art Wolfe and Frans Lanting — donated images to the cause, under the name “Wildlife Photographers United.”

The resulting book, “Remembering Elephants,” became a runaway success, and Raggett went on to continue the project with “Remembering Rhinos” and “Remembering Great Apes” — the latter of which included a foreword from the late Jane Goodall.

Every year since, Raggett has galvanized a team of photographers to support the conservation efforts in countries around the world, with proceeds going to vulnerable and endangered species like lions, cheetahs, African wild dogs, polar bears, leopards, and tigers.

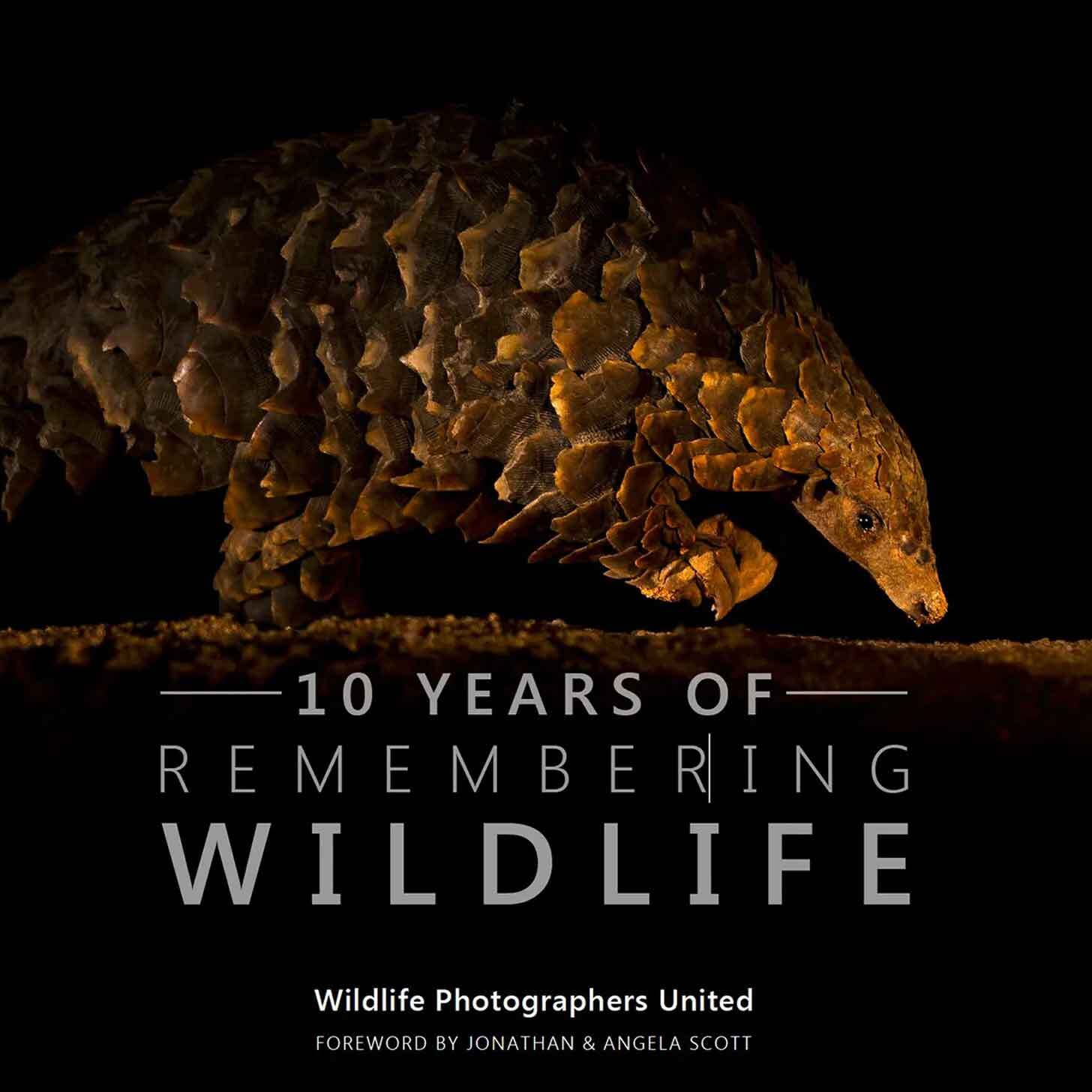

And now, they are celebrating the release of their latest book: “10 Years of Remembering Wildlife.”

Alongside photos from the previous nine books — that were voted on via a “best of” competition — the book features 20 new photographs and opens with a chapter that highlights the plight of the world’s most trafficked mammal: the pangolin.

Remembering Wildlife is transparent about where its money goes. On the landing page of their website, they break down exactly what happens with every cent.

Every book is prefunded by Kickstarter, supported by the public. And the photos themselves are donated by “300 of the world's best wildlife photographers.”

“All of the stunning images we use in our books and exhibitions have been generously donated by our photographers, as their way to give back to the species they make their livings from photographing,” the business writes.

They reference keeping “overheads” as low as possible, all while paying their core team to design, edit, and distribute the books.

Even then, the company emphasizes that everyone is “receiving considerably less than they would in the commercial world” because they believe in the cause.

And it’s working.

“So far, we’ve distributed more than £1.23m GBP ($1.58 million USD) of ‘profit’ to 80 different conservation projects in 34 countries since we started in September 2015, and we are determined to grow that,” they pledge.

“Time is running out for so many species that we believe being as nimble as we can is critical to getting funds raised out into the field,” they continue.

“Unlike the way many charities operate, we don’t sit on big reserves of cash or schedule donations months or even years ahead; we want our cash out with projects doing good as soon as we possibly can get it there.”

In her interview with Bob Books, Raggett talked about the dichotomy of wildlife photography, from the reality of poaching and the decline of endangered species, to the celebration of these magnificent animals.

“I think there are two different approaches, and I talk a little bit about it in my introduction to the … book ‘Remembering Great Apes.’” Raggett said.

“First, there are obviously the shocking pictures, which make people turn away in horror. In these books, I’ve been very selective in illustrating the problem and the vast majority of what we have in the books are the beautiful pictures of the animals in the wild, because that’s what I believe people want to buy.”

“But,” she said, “I called the books ‘Remembering…’ and there are a couple of reasons for this.”

“Around the time I was thinking about doing the book, I saw an interview with Jane Goodall on the BBC and she was talking about the elephant poaching crisis,” Raggett explained.

“She was quoting some statistics showing that elephants were being wiped out quicker than they were being born and were on a path to disappearing. I just thought how shocking it was that it could happen on our watch and that our generation could be the last to see elephants in the wild.”

Ultimately, Raggett said, the project is about balancing the reality of the threats facing endangered species — and also capturing their beauty before it’s too late.

“I also think it’s important to show people the good side, because many people don’t have the opportunity or funds to travel to the places where these animals are still wild,” Raggett said.

“So through wildlife photography, we’re able to show them what we stand to lose if we don’t do something about it.”

You may also like: This deadly virus is the 'silent killer' of young elephants. A new vaccine rolls out to save them worldwide

Header image via Julie Oldroyd/Remembering Wildlife